In organizational life, bad things don't just happen. They tend to follow a pattern, especially over time. In seeking a means of categorizing these events on the path to doing something meaningful about managing them, it may avail to look at them through the prism of what I call the Untoward Event Matrix.

What It Is

This matrix represents a rough ordering of undesired events according to their impact and frequency of occurrence. Using this tool is akin to plotting things on a piece of graph paper to show their relative position. The exercise necessarily involves artificiality; yet it may prove illuminating in showing how the items plotted relate to each other. It may even offer visibility into where to invest energy and resources to reduce loss.

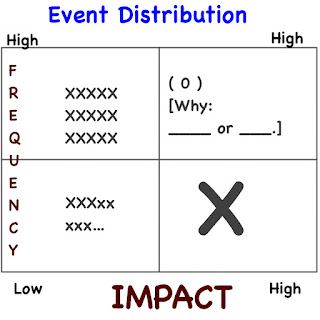

As a starting point, divide the matrix into quadrants, like this:

Now there are only four boxes to fill, going from the bottom up and then to the right:

LOW FREQUENCY/LOW IMPACT

These are undesired events which seldom occur but hardly matter in terms of hurting the organization. A brief, occasional power outage or random, minor accident could fall into this category.

HIGH FREQUENCY/LOW IMPACT

These are undesired events which occur more often, to the point of becoming predictable. While their impact is also relatively low, such untoward events tend to raise eyebrows if they cause cumulative losses or disruptions whose impact could cross over from low to something more severe. Think of recurring graffiti, vandalism, and accidents or mugging that, over time, flag a given site as unsafe.

LOW FREQUENCY/HIGH IMPACT

These are game-changers that are focusing events because, although statistically rare, their severe impact makes a devastating mark on the organization. Think in terms of a 9/11 attack or massacre at the workplace.

HIGH FREQUENCY/HIGH IMPACT

Such events represent a theoretical worst case scenario, because they combine the severity of the previous category with a high incidence of occurrence. If, instead of being rare, such events become commonplace, they create an unsurvivable situation. Consequently, in the real world of corporate life, such conditions are more abstract than realistic. Why? The people in charge realize that they face a simple dilemma: fix or die. In other words, if they cannot drive down the frequency of high impact events to being rare, hence low frequency, they cease to remain in business.

Depiction

This is how the situation looks in practice, after consulting the organization's own incident reports to see how untoward events tend to array across this matrix over time:

Whence the Data?In the corporate world, as in large public sector and nonprofit organizations, it behooves management to monitor untoward events, the better to limit losses and to gauge what insurance to seek out as a means of transferring risk. Accordingly, some office in the organization takes on the responsibility of tracking incidents, typically with the aid of an incident reporting system. Data from such incident reports, in turn, inform the distribution of events (aka incidents) captured broadly in the foregoing matrix.

What Happens Next?

Once management discerns the emerging pattern showing the frequency and impact of untoward events, competent managers begin to do what they do best: prioritize.

First, they attack the biggest, most immediate challenge, the big X representing the high impact/low frequency event that just befell the organization or threatens to surface in the near future. Certain possibilities soon confront them:

(A) This event has reached catastrophic proportions and is requiring a no-holds-barred, all-hands-on-deck response;

(B) The worst impact of the event is over, leaving management to clean up, restore operations, and learn lessons to apply in reducing future impacts of a similar event; or

(C) The likelihood or severity of the event taking place has diminished to the point of making it a non-issue, leaving no budget or executive support for pursuing it further.

Shifting Focus

Under the circumstances, once the most urgent priority, the big X, goes away, lesser priorities get a promotion. Accordingly, those resources once tasked with resolving the big X now shift, as shown here:

Why? It is the nature of humans and their organizations to harness their capabilities to those challenges deemed important, or perhaps urgent. Failing that, they default to tackling the challenges at hand. Consequently, organizational focus now turns to untoward events that may be of lesser impact yet remain of sufficiently high frequency to open the door to the possibility that, if neglected, they could eventually cross over into one of the two high impact quadrants of the matrix.

Defender Predicament

It now becomes the defender's dilemma to at once address the high frequency/low impact events while keeping in reserve some capacity to handle potential high impact events that will most likely be rare. Why? The unchecked arrival of those high impact events, especially if allowed to also become high frequency, might be fatal to the organization.

Conclusion

This is only one way of using the untoward event matrix to apprehend ambient risk and contrive plans for where to focus resources available for mitigation and prevention. A seasoned manager with corporate experience will no doubt find more. Why? Because bad things don't just happen, and good managers don't wait to be surprised by them.